Legacy Is Our Future

1894 – 1895

They were duly placated when Watkin offered them more land and rehabilitated the entire grounds. The war with the opposition of his plans took its toll financially and on his health. He suffered a heart attack before construction of the railway began in 1894 and Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Wharncliffe (the serving Vice Chairman) took over his role.

Sir Edward Watkin was in attendance at the opening ceremony of Marylebone station and of the hotel but died only two years later in 1901.

He took the enterprise one step further by installing a Maples shop in Marylebone station that way if guests of the hotel liked the furniture they could go over to the station to buy it.

1897 – 1899

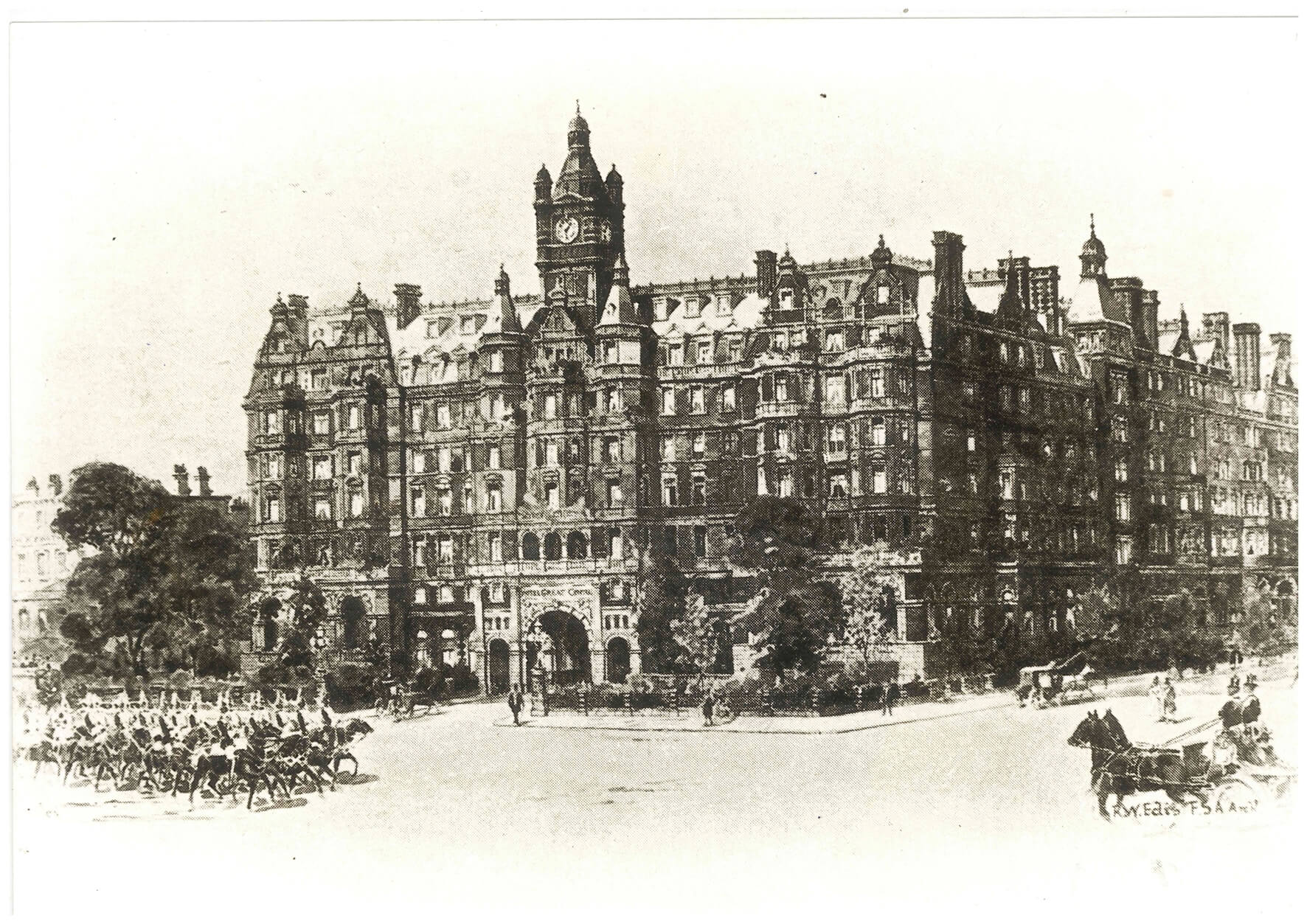

1899 –The Great Central Railway opened for passengers on the 9th March 1899; Sir Edward Watkin was in attendance with his successor Edward Montagu, the Earl of Wharncliffe. Montagu died aged 72 in May of that year. He must have been a beloved figure as when the hotel opened they named the ballroom the Wharncliffe Rooms after him.

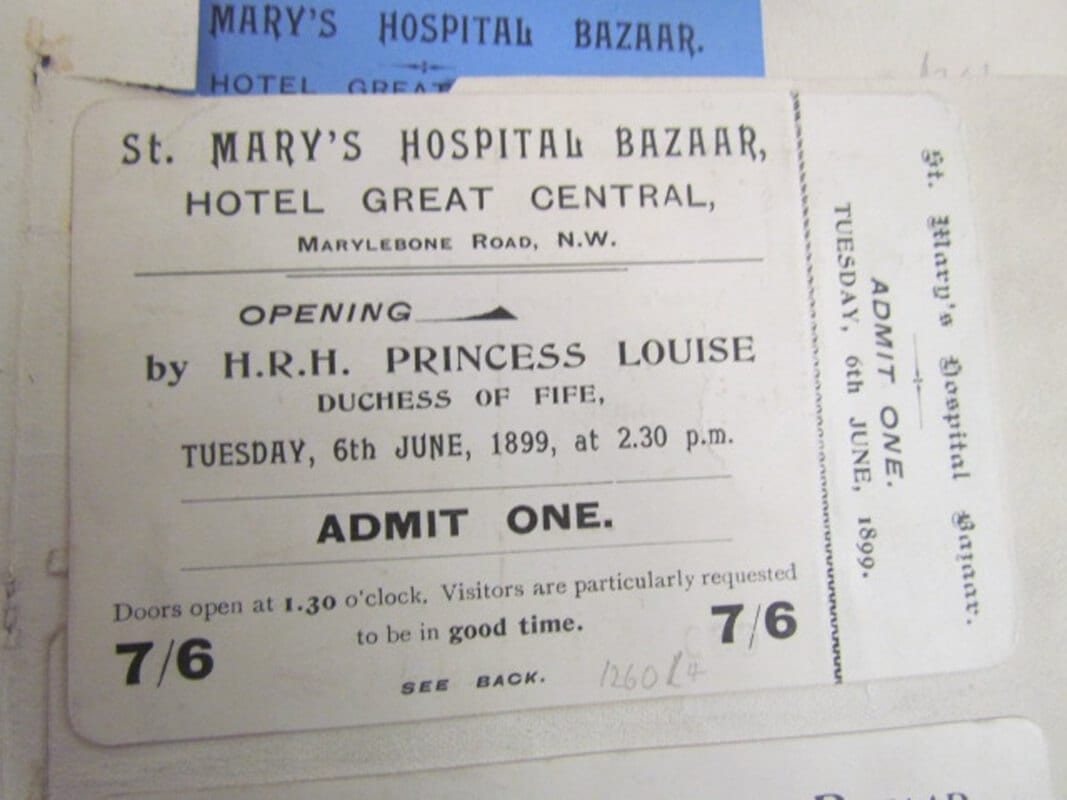

The whole ground floor was decorated especially and given free of charge to the event. The Great Central Hotel also provided refreshments. The reason was to raise money to build a new wing at St. Mary’s Hospital. Members of the board at St Mary’s Hospital nominated the ‘centres’ and representatives to take part. ‘Centres’ referred to different communities of London that were invited to provide for a stall either through subscriptions, donations or gifts in kind to sell. The Westbourne Terrace stall sold paintings by eminent artists as listed on their advert. Other ‘centres’ that took part were Hampstead, Grosvenor Square and Mayfair, Gloucester Terrace and Kensington Palace Gardens. There were over 40 in total.

The hotel opened officially on 1st July 1899 and rooms cost three-and-sixpence a night.

1902 – 1908

In October 1902 the first service was held in the Wharncliffe Rooms at the Great Central Hotel for 300 people with policeman guards at the entrance in case of any civil unrest. Dr. Claude Montefiore delivered the service frequently making references to ‘Jews and Jewes’. The JRU went on to become the Union of Liberal and Progressive Synagogues and still exists today.

1906 – Gertrude Wainwright was born in 1876 in Yorkshire, her mother was a teacher and a widow and she had two brothers Harry and Frederick that both worked as Railway Clerks. The 1891 census reveals that Gertrude was training as a milliner’s apprentice.

Ten years later the 1901 census lists Gertrude as unemployed and living with 14 others in Manchester Street, Paddington.

On the 10th July 1906 she gave birth in the Great Central Hotel to a boy, Samuel Paget and no father was registered on the birth certificate. She was 30 years old. By this time she had moved to 16 Sydney Place in South Kensington. It was extremely uncommon for ladies of that era to be staying in hotels alone. How could the unemployed daughter of a widow afford such extravagance?

Could Samuel be Richard’s illegitimate son?

1908 – In the early 1900’s a group of women known as the Suffragette’s were lobbying the government to give women the right to vote. The leader of this political movement was Emily Pankhurst along with her daughters.

On the 19th March 1908, Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst was released from Holloway prison where she and other women were being held as political prisoners. In a meeting of the Suffragettes at The Royal Albert Hall later that day a speech was transcribed and it stated that the Great Central Hotel was holding a “Welcome Back from Prison” breakfast for Mrs Pankhurst and the other Suffragettes.

Between 1902 and 1910 major changes were made to the design of the courtyard. Large winter gardens had been brought in to fashion and the central courtyard must have proved unsuitable in an age of growing car use. The entrance to the courtyard was thus blocked up and the entire central space was turned in to a huge winter garden. A dance floor was installed in the centre.

1914 – 1956

1918 – The Great War only represented a temporary change of use for the building as hotel business was resumed soon after.

1935 – After the Great War Mr Paul Paquot was the Hotel Manager. The decade was known as the height of glamour and hedonism and Paul got carried away. When the depression arrived, bringing depths of anxiety and despair, Paul’s life echoed what was happening in society and he was declared bankrupt in 1930. Only five years later he was found dead.

What makes this intriguing is that some guests have claimed to of seen the ghost of a man wearing a sharp 1930’s pinstripe suit and hat on the 4th Floor.

1939 – The legendary British Lieutenant Airey Neave, was the first British soldier to escape from Colditz on January 5th 1942. Neave crawled through a hole in a camp theatre after a prisoner performance to a guardhouse, then boldly marched out dressed as a German soldier reaching Switzerland two days later. Upon his return to Great Britain, Neave reported to the Great Central Hotel where escapers and evaders were debriefed by MI9 in the hope of helping other Allied Troops escape. Throughout WW2 MI9 were responsible for bringing 3000 people home safely.

Airey had been to the Great Central Hotel before and was quoted saying, “Before the war, the Great Central Hotel held a strong attraction for me. I was drawn to the magnificent dullness and solidity of the hotel. I liked the brass bedsteads, the marble figures on the stairs and the massive afternoon tea. Outside this refuge my young world was threatened by Hitler. Inside, I could pretend that I belonged to a safer age.” Neave later joined MI9 and went on to lead the campaign that got Margaret Thatcher in to office.

In March 1979, Airey Neave was assassinated in the car park of the House of Commons one month before Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister.

1941 – In WW2 the Nazis had recognised the importance of propaganda. The British were reluctant to see advantages and did not like the idea of their tactical blunders being recorded and photographs of British soldier corpses being made available to the public. America exerted pressure to record the war and British Diplomats in unoccupied countries reported that Nazi propaganda was gaining support. It is for this reason the Army Film & Photographic Unit was formed.

In 1941 troops were interviewed, recruited and billeted at The Great Central hotel, Marylebone for up to 4 months while rudimentary field training was held at Pinewood Studios and in Green Park. In 1943 the unit used footage filmed during real battles to make Desert Victory and the film went on to become the third most popular of the year. Churchill was delighted with the film and said that ‘it excited the greatest admiration and enthusiasm throughout the Allied world and brought us all closer together in our common task’

The Irishman was stripped and searched, revealing a tattoo under his left armpit. It was a small, simple marking, consisting of no more than a letter ‘A’, but its significance was far more serious. The practice of tattooing a blood group in this manner was generally associated with the SS. After interrogation the Irishman was revealed to be James Brady.

James Brady originally joined an Irish regiment of the British Army and but for a twist of fate would have ended up fighting against the Nazi’s. Instead, having been captured by the Germans in Guernsey, he switched sides and was trained by German military intelligence. He was recruited to the German Special forces.

In 1946, Brady was tried by the court-martial in London; it is safe to assume he was stationed in the hotel whilst in England. James Brady was found guilty and sentenced to 15 years.

In 1945 the London and North Eastern Railway Company had a shortage of office space as their own building had been lost to the Blitz and so bought the building from Frederick Hotels (later Frederick Hotels joined Trust House Forte THF which later became the Forte Group). In 1947 architectural maps held at the National Archives show plans for restoration ordered by LNER. Interestingly, what was originally the Billiards Room for gentlemen (now our Great Central Bar and Restaurant) was recorded as the staff dance hall and for every year that the building was used for railway offices, Music and Dancing Licences were purchased.

1949 – The nationalisation of the railways meant the LNER became the British Transport Commission.

1956 – In 1956 the British Transport Commission, which later became British Rail, initiated the main conversion work. It was around this time that the central courtyard roof, Edis statement of luxury and grandeur, was removed and the Winter Garden temporarily open to the elements. The building gained the nickname ‘the Kremlin’.

A newspaper article stated that the ballroom was being used as a basketball court. Ex staff of British Rail, now retired, told us that there was a canteen, an officer’s mess and a senior officer’s mess with a bar for meals in what are now our event spaces.

1988 – Today

In 1991 a new design proposal was submitted and at this stage the new roof to the atrium was erected, the stairs in the lobby were installed and the Marylebone Road entrance was raised. The new design for the Winter Garden considered every detail of the spaces encountered from entering the building, up two flights of steps into stone clad arches to establish an image and manner of decorum befitting the grandeur of the hotel while also heightening the expectation for the drama and experience of the soaring Winter Garden. The proposed name for the new hotel was to be the Windsor Hotel.

1993 – The hotel reopened as the Regent and was part of the Four Seasons Group. Fittingly His Grace James Carnegie, the 3rd Duke of Fife was in attendance. James Carnegie is the grandson of RH Princess Louise, Duchess of Fife.

1995 – Bought by the Lancaster London Hotel Company and renamed the Landmark London Hotel.

2008 – Becomes a member of the Leading Hotels of the World.